The first time we met to talk about this exhibition was in February 2019. We were in Berlin and would meet again a few months later in Parma. The desire was to bring together Goya’s Caprichos with the drawings and paintings of George Grosz. The disruptive social satire, political commitment, moral prominence and extreme formal innovation that the works of the two great painters have in common seemed to us to be the foundations on which to base our project. Two artists who, one hundred and fi fty years apart, changed the course of art history by following individual itineraries of absolute originality, always one step ahead of their contemporaries, but deeply rooted in the times and societies to which their work was directed.

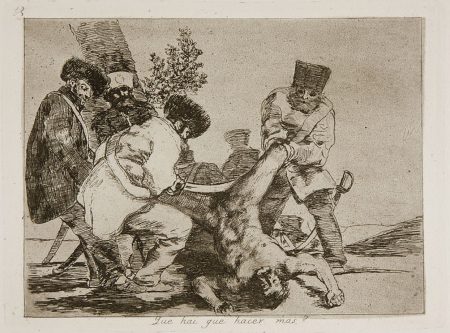

Then, the pandemic locked us at home, showing how fragile our world was. And the pandemic was followed by war in Europe, which no longer seemed possible to us. Somehow, the Belle Epoque we were experiencing has crumbled and the ghosts and nightmares of a past that we believed to be buried have resurfaced before our eyes. So, even if current events haven’t changed our plans, they’ve undoubtedly cast a different light, both on each of the works we were planning to exhibit and on the exhibition as a whole, for all the vices and perversions painted by Goya and Grosz have certainly not disappeared, but are still and always poisoning our days. Ignorance and worldly chatter, the abuses of the powerful and the hypocrisy of the Pharisees, false science and real fraud, the violence of the aggressors and the suffering of the victims, the ostentation of wealth and the resignation to misery seem to be undated.

In fact, everything changed so that little or nothing would change. Goya’s engravings and Grosz’s paintings do not tell us about ancient history, but about the history we are living every day. The sleep of reason and the monsters it produces are always the same, be it in 1799-Madrid or 1920s’ Berlin, or the entire West today.

The only real novelties of our time are technical tools. In this 21st century, the dream of reason is trying to definitively replace thought with calculation, human intelligence with artificial intelligence and the work of the hand with that of the machine. Consequently, even in the fi eld of art, we are witnessing the progressive substitution of drawing, engraving, painting, sculpture and even photography with virtual images, the mere result of alphanumeric codes, devoid of all physicality and deprived of the artist’s gesture.

In such a context, it seemed important to us to focus not only on the works’ content, but also on their form. On the outstanding skill of two of the greatest draughtsmen of all time, on their ability to reveal profound truths with just a few strokes of ink, on the sharpness of their gaze and the width of their visions contained in the work of the burin or in the brushstrokes of colour, in short on that ‘thinking with the hands’ that has been the very substance of fi ne arts since the dawn of time.